|

| Cover Story |

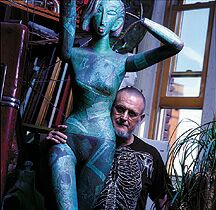

SURREAL THING ECCENTRIC ARTIST AND COLLECTOR STEVE SMITH BARES ALL by Amy Bracken Sparks |

Smith's dog story is anything but shaggy.

After a night of revelry, the man simply called Smith was lurching his way home through his inner-city neighborhood. An energetic artist and excessive drunk who no longer drove his highly corroded and decorated Saab, Smith was walking behind his mother, affectionately known as Mother Dwarf. Both mother and son had auctioned off pieces of their art at a local art auction, and Smith had exuberantly bid on almost every other piece of art offered. The accounting would be done later, at a clearer time.

Passing a fenced-in yard, Smith was attracted by the sound of loud, barking dogs, to which he responded instinctively. He approached the fence and began to howl in communion. But his six-foot-three-inch body drifted into dog airspace and they responded with teeth on flesh. Bleeding profusely from his scalp, Smith ambled home. The next day, he asked his mother why he was covered in blood. Mother Dwarf responded, "You mean ... you don't remember the dogs?" Smith loves to tell this story, and many others, about his outraged and outrageous life. He leans over, pointing out the permanent scar on his head, a mark God surely will pass right over. As if he cared: Smith is as disdainful of organized religion as he is of the new designer drugs ("they're boring"). If Cleveland ever celebrates its eccentrics, Steven B. Smith will be in the top five. A former art gadfly present anywhere art, poetry or partying was happening, Smith is now a recluse whose doormat says Go Away. A western farm boy who once married into an East Coast, blue-blood family, Smith's life stories roughly equal the amount of movies he's collected: 3174. Smith loves words, puns, numbers and movies. He stole 13 cars when he was thirteen, was a sailor, a life insurance salesman, a programmer analyst, a carnival laborer and church janitor. He was kicked out of the Naval Academy at Annapolis for smoking marijuana in 1968, but received a college education from the government anyway. He was married, divorced, took every available drug for years, delivered milk, worked at Bethlehem Steel and, oh, almost died. He's also a prolific artist, poet, editor, movie and comic book collector, who, at age 54, has the face he's "earned." "The Chinese say that until you're fifty, you have the face you're born with. After fifty, you have the face you've earned. "I'm in the spaces between the pages," says Smith, now a thin man with a shaved head and Amish beard. His voice is raspy "because I don't talk to anyone anymore." We're in his Tremont condo where he lives with his mom. (She relocated to Cleveland from Las Vegas after both her son and husband died.) He's wearing a black T-shirt with a screenprint image of a man's skeletal torso on it. It suits his back-from-the-dead mindset. He has the energy of five men and talks rapidly, jumping from subject to subject as his mind makes connections that at first seem incomprehensible. Eagerly, his stories cascade one on top of the other. His one link with the world, his computer, sits quietly in the corner. In 1985, when he first moved in, he had far too much stuff. Much of it was given, traded or thrown away. An enormous pile of papers, paintings, mannequin body parts, books and more commanded the center of the room. About this pile he tells another story: "After my brother died, I was sitting here, staring at the pile. A faint beeping began and I couldn't figure out where it was coming from. I checked the windows, the corners. Then I realized the beeping was the soul of my brother." He pauses, waiting for my reaction. "It was the worn-out smoke detector at the bottom of the pile," he says, cackling. His unique mixed-media artwork is hung salon-style to the ceiling. A freelance computer programmer - he formerly contracted with BP - he's now between jobs. He'll often watch up to six movies a day, only interrupted by visiting his mother in the county nursing home, where she's recovering from injuries incurred when she was run down recently at the West Side Market. "She better recover in time for baseball season," he says. It wasn't always this way. Long before he stopped drinking and driving, Smith was active in Cleveland's burgeoning art scene, taking potshots from the fringe. One of the first artists to live in the Bradley Building in the Warehouse District, Smith used his former warehouse space as a, well, warehouse, paying less than 300 bucks for 3000 square feet in the early 1980s. Rows and rows of metal racks held mannequin parts and doll heads, plastic molds and chicken feet, kitschy pictures of the Virgin Mary, toy soldiers, comic books and flags, poems, papers and old frames - all fodder for his mixed-media collages, which he frequently slathered with copper sulfate to achieve a tarnished patina. If you were a guest, you always got a present to take home. At the time, Spaces gallery was located on the building's first floor, acting as "the epicenter," as he puts it, "for a lot of creative activity." Smith can rightly be included in the loose group of artists, musicians and renegades who reveled in Cleveland's industrial beauty and undeveloped Flats in the late 1970s and early '80s. That's when the Powerhouse was a ghostly, abandoned hulk, and the only action on the east bank was a gritty bar called Pirate's Cove (now Peabody's) showcasing an unknown band named Pere Ubu. "I have a story about Pirate's Cove," he says, which is not surprising since he has stories about everything. "My boss at the time wanted an art piece made from the hood of a car. We had it taken to the second floor of Pirate's Cove where a couple guys with Uzis shot holes in it. There we were, in suits, watching guys puncture the car hood with machine guns," he says, laughing at the memory. "People downstairs had us stop. It was breaking up the bricks and stuff." When not making art or staying up all night partying, he was writing clever, punning poetry and reading it all over town, attending every possible art opening and making eyebrow-raising works for Cleveland State University's People's Art Show - works that primarily involved images of his own genitals in proximity to the American flag. He started a literary/art zine called ArtCrimes and participated in a couple of legendary "art terrorist" raids in the Flats. He was a regular visitor to the Cleveland Cinematheque when it opened, and could usually be seen at $2 Mondays at the Cedar Lee Theatre. And then there was the drinking. He laughs when retelling horrific stories of his last days of drinking. There's the crashing-his-car story, the tearing-down-the-"bad art"-and-getting-beat-up-by-the-cops story and the Mortal Thoughts story, which is the last and most ironic. "I was a good drunk and didn't kill anyone, but I was on the way to killing myself," he says. "But when they put tubes up my nose [in the hospital] I realized I'd never drink again. "Ma and I were downtown seeing Mortal Thoughts when I noticed I kept swallowing liquid. But I wasn't drinking anything. After the movie I realized I was swallowing blood." Smith spent the next 14 hours in and out of consciousness, vomiting blood and passing out before going to the hospital: "I kept looking at this bucket of blood collecting next to my bed, and wondered how I could use it in a piece." But it was not to be. Smith received six pints of new blood when he got to the hospital. It turns out he was bleeding from his esophagus - "the same way Jack Kerouac died," he says with awe. "That was April 21, 1991, and I haven't had a drink since." He pauses. "I really miss black coffee and cognac, and the mere act of looking at wine in front of a fire. I also miss art openings and poetry readings and going to the Cinematheque," which is a two-hour bus ride away. Coincidentally, though Smith believes nothing in his life happens by chance, in April 1991 he bought his first movie - Orson Welles' Touch of Evil - exchanging one excess for another. (Smith rejects the notion of substituting one obsession for another; don't even ask him about Alcoholics Anonymous.) "Nobody else has the breadth of trash and class I do." Bride of Re-Animator sits alongside Betty Boop: Boop Oop A Doop next to Broadcast News. He has documentaries on T. S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens, two of his favorite poets, as well as almost everything Robert Mitchum has ever done. "If I could be anybody else," he says, "I'd be Robert Mitchum." Primarily English-language films, with notable exceptions such as Shohei Imamura's 1963 Insect Woman, a half-dozen Antonionis, a foursome by Emil Cohl dating from 1909 to 1912 and a solid selection of Cocteau, Truffaut and Godard, Smith's collection is eclectic and personal. He has a penchant for obtaining originals and their remakes. "Invariably," he says, "the original has a hard moral lesson that the remake ignores." His collection goes back to 1894 with three films by the brothers Lumiere, credited with inventing modern cinema. His favorite director? Ingmar Bergman. His favorite film? He mentions Bergman's 1950s circus film, Sawdust and Tinsel, a three-minute film by David Lynch called Alphabet and a five-minute film called Anemic Cinema made in 1926 by Marcel Duchamp. He's very much influenced by the surrealists Dali and Bunuel, but for a single favorite film, he can't decide between Carol Reed's The Third Man and Michael Curtiz's Casablanca, fairly mainstream choices for a man whose entire life has been about challenging the status quo. But his idol is Lenny Bruce, well known for his lobs over the foul line. "I love the glitches you sometimes get in these video copies. I got a copy of L. Q. Jones' A Boy and his Dog, and it contained a thirty-minute film of diseased vaginas on it, a short film called Vulva Vaginitis," he notes with glee. "So I returned it and got another. And it was the same. So I returned that one, and got a clean copy. Now I wished I'd kept a faulty one." He breaks his life into lists. His resume is sectioned into decades; his deeds and misdeeds listed alongside his many jobs and various states of being. A sampling:

1960s 1970s His vast and varied collections are highly organized in racks and racks of videos arranged primarily by director, as well as countless books, journals and 600 comic books going back to 1950, including first editions of "House of Secrets" and "House of Mystery," and primo copies of "Swamp Thing" and "Howard the Duck." He also has 2000 45s, 1000 tapes and 700 CDs arranged according to systems only Smith understands.

His vast and varied collections are highly organized in racks and racks of videos arranged primarily by director, as well as countless books, journals and 600 comic books going back to 1950, including first editions of "House of Secrets" and "House of Mystery," and primo copies of "Swamp Thing" and "Howard the Duck." He also has 2000 45s, 1000 tapes and 700 CDs arranged according to systems only Smith understands.

His space, which he shared with his brother, Cat Smith, was a gathering spot for other artists in the building, including S. Judson Wilcox, Melissa J. Craig (AKA "May Midwest"), Laszlo Gyorki, Ken Nevadomi, Randy Rigutto, Jay Clements, Beth Wolfe and more.

His space, which he shared with his brother, Cat Smith, was a gathering spot for other artists in the building, including S. Judson Wilcox, Melissa J. Craig (AKA "May Midwest"), Laszlo Gyorki, Ken Nevadomi, Randy Rigutto, Jay Clements, Beth Wolfe and more.

The print-out is enormous: 76 single-spaced pages list the movie titles Smith owns. Heavy on the Hitchcock (44), Bergman (26), Bunuel (18), Fellini (12), Roger Corman (20) and animation, it's a chaotic list of high art and pulpy entertainment. Crossing boundaries has been Smith's way of life, and his collection reflects it.

The print-out is enormous: 76 single-spaced pages list the movie titles Smith owns. Heavy on the Hitchcock (44), Bergman (26), Bunuel (18), Fellini (12), Roger Corman (20) and animation, it's a chaotic list of high art and pulpy entertainment. Crossing boundaries has been Smith's way of life, and his collection reflects it.

A self-actualized man who has grown into his own myth, Smith was born in Wallace, Idaho, twenty miles outside of Spokane, in a place called Paradise Prairie. These places are symbolic to him today: Wallace Stevens is his favorite poet ("I'm Wallace Stevens' Myth"), and Paradise Prairie is a place lost in time, out of which he emerged, speaking.

A self-actualized man who has grown into his own myth, Smith was born in Wallace, Idaho, twenty miles outside of Spokane, in a place called Paradise Prairie. These places are symbolic to him today: Wallace Stevens is his favorite poet ("I'm Wallace Stevens' Myth"), and Paradise Prairie is a place lost in time, out of which he emerged, speaking.

1950s

farm boy

cow milker

chicken/rabbit/hog waste remover

hod carrier

paper boy

car thief

electronics technician

poet

USNA midshipman

artist

husband

chemist

prison cook

bankrupt

avant-garde theatre manager

newspaper film/music critic

women's shoe salesman

adulterer

divorced

In the 1980s he was drunk and celibate, a condo owner, publisher and programmer. The 1990s have been quiet, even contemplative: near dead, sober, european traveler, unemployed.

During our interview, Smith sets out the cardboard box containing the remains of his brother, who killed himself at age 30 in 1987. "He owes me money," Smith explains, "so I want him to hear this."

In a late '80s exhibition at Spaces, Smith put the plastic bag of Cat's ashes on a pedestal. Somehow, the fragile bag was punctured ("by a friend of mine," he says). Ashes spilled out onto the pedestal and the floor.

"Someone from the gallery called me in tears, telling me that something terrible happened to my brother. When I got downstairs and saw the spilled ashes, I was thrilled," he says. "It was great."

When I remind him that he offered ashes to many of us the night of the opening, he just shakes his head: "I don't remember that."

Cat Smith was also a gifted artist. His small, more modest and subtle collages are on display in the cluttered bottom floor of the condo. They are dead ringers for the renowned collages of important German artist Kurt Schwitters.

Smith's father, called "Pappy," also made a collage before he died. It's comprised of Cat's old masonry tools, rusty and fixed forever. The condo's bathroom is the realm of Mother Dwarf Smith; her kitschy, more light-hearted collages adorn every nook and cranny. Taking cues from her son, but using sweeter materials, she has made cheery works that only hint at the losses in her life.

Smith's father, called "Pappy," also made a collage before he died. It's comprised of Cat's old masonry tools, rusty and fixed forever. The condo's bathroom is the realm of Mother Dwarf Smith; her kitschy, more light-hearted collages adorn every nook and cranny. Taking cues from her son, but using sweeter materials, she has made cheery works that only hint at the losses in her life.

Before moving to visual art, sculpture and zine publishing, Smith began piecing his life together in thick, unique journals into which he stuffed, cut apart and juxtaposed images and text and poetry alongside daily notations of politics and personal musings. The one from 1973-75 quotes extensively from Black Uriah and Diogenes, and contains the Tibetan chant he still chants daily, scraps of writing, drunken proclamations and news of the day: "Kennedy is out of the '76 race. Rockefeller hearings focus on finances, pardon, taxes." Beneath the news is the "masochist's motto: To Thine Own Self Be Cruel."

Entire tiny comics are folded within its pages; pieces of his bluejeans run along the seams. A highly collectible cover of the serial Weird Tales stares down a somber photo of Wallace Stevens. A graduation photo of Smith (he attended Loyola University in Baltimore majoring in English and philosophy; "those Jesuits were okay") is backed by a photo of him as a freckly-faced kid in gingham. Beneath those is the famous M. C. Escher print of people perpetually climbing stairs. "That's my mind," he says, pointing.

Some pages are backed with burlap or other fabric. A devotional section combines images of Marilyn Monroe, Elvis and personal friends. A note to himself: "i must write i must write i must write" followed by "he did not write he did not write he did not write..."

The cover of the recalled Beatles album Yesterday and Today - with the Beatles cradling pieces of raw meat and baby mannequins in their arms - has been cut up to fit Smith's journal format. Popeye and Picasso get equal billing, and in between the uncharacteristically sweet scenes of bunnies and old-fashioned general stores and a boy dressed in blue are the kernels of what would become Smith's fascination with wordplay and a humorously dark vision of the world. The front and back covers are cut from the shirt of Smith's naval uniform. It's a glorious artifact of the times: a personal, political, reverent and irreverent document of American pop culture by an educated outsider.

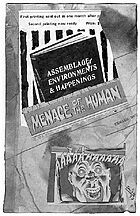

His collaged journals would later inspire the various formats of ArtCrimes, the unpredictable zine featuring poems and Xerox collages by area writers and artists. The first was published in 1986, featured work by 28 artists and was called If Indication Abnormal. Later editions of the zine were guest-edited and took various forms: a coloring book, a box of loose pages, a video, a legal pad and the official Performance Art Festival catalog for 1989. The 18th edition is a solo work by Smith called Burnt Tongue Soup - Word Smiths Words Worst, a collectible in itself. All have been financed by Smith, with copies numbering between 120 and 400. An upcoming 20th edition has just been planned.

What brought him to Cleveland? "Another man's wife," he says with a grin.

What got him into computers? "In 1975 I was in Baltimore, and I was sick of selling women's shoes when I had a revelation in an alley on LSD: that the future was in computers. I talked my way into National Cash Register's mailroom. Two weeks later they made me a computer operator, and six months later I was third shift leader with five people working for me."

What made him a recluse? "I had to learn silence," he says. "People only remember the old days when I shocked people with what I said or made or did. But there's a lot of beauty in the things I've done.

"I believe I'm in an apprenticeship that has taken me this far. I'm lucky. I live to reduce self-loathing, and make things around me better. I'll always make art. There is no cut-off point for that."

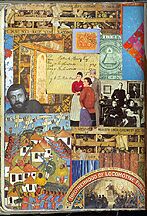

His artwork rambles from the sublime to the ridiculous. His first collage was completely comprised of words and letters. Through the years he's replaced text with images, added sculptural elements such as crucifixes, dead mice and mirrors and, sometimes to their horror, other people's art. Some of his work looks like abstract paintings of oxidized copper. Other pieces are quite rhetorical and bombastic.

His artwork rambles from the sublime to the ridiculous. His first collage was completely comprised of words and letters. Through the years he's replaced text with images, added sculptural elements such as crucifixes, dead mice and mirrors and, sometimes to their horror, other people's art. Some of his work looks like abstract paintings of oxidized copper. Other pieces are quite rhetorical and bombastic.

He returns again and again to politics as a touchstone; investigates loss and loneliness; and makes quite a few ironic jokes. His collages are raw and powerful and cracked wide open. There are no secrets in Smith's life. You can see that in his work. "My art is a collaboration with the pieces," he explains.

A commentator on Smith's website describes his art this way: "[It] bursts out of the aesthetic realm and confronts religion treated as empty formality, along with other modern horrors like war, gossip, dishonesty and torn human relationships. Some of Smith's fantasies are part of public domain, some are intensely personal, but all are unremitting and barbed with wit."

Smith admits he'd love to break the visual silence and show his work again somewhere. Lately, his works for sale and pieces of his life story are posted on his website, and you can reach him at his AgentOfChaos web site.

But it's not nearly enough to fill in the gaps.

"My life," he says, "is more interesting than I am."

Smith Home | Collage | ArtCrimes | Mutant Bio | Poetry | Next Newspaper Article