Cleveland Free Times 5.11-17.2005 article by Lyz Bly - foto by son of Dwarf

|

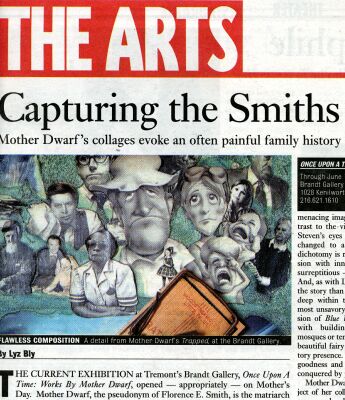

Capturing the Smiths Mother Dwarf's collages evoke an often painful family history by Lyz Bly Cleveland Free Times May 11, 2005 The current exhibition at Tremont's Brandt Gallery, Once Upon A Time: Works By Mother Dwarf, opened - appropriately - on Mother's Day. Mother Dwarf, the pseudonym of Florence E. Smith, is the matriarch of the highly creative and prolific Smith family. While there were originally four Smiths in her clan - Mother Dwarf's husband Ralph, and son Vincent, passed away; two remain, Florence and her son Steven. Steven is known as the self-described "agent of chaos" behind the cult classic art and poetry journal ArtCrimes, which marks its 20th anniversary in 2006. According to Steven, his mother began her art career by producing collages for ArtCrimes. "My entire family made art for the journal," he explained. None of the Smiths are trained artists; instead, they rely on an inherent eye for composition. At age 68, Mother Dwarf had her first solo exhibition. Once Upon A Time is her fourth solo show; she is now 79. "Often, people like my mother's work better than mine," says Smith. "Her work isn't as dark as my collages are." While this may be true, that does not mean that Mother Dwarf's collages abound in cutesy, cheery images. You won't find dewy-eyed, fluffy kittens or cherubic pink babies in her work. Instead, her collages evoke the life of a complex, powerful woman. At age 79, she has a great deal to say about her personal history. Her work is both personal and universal; it reveals the intricacies of American womanhood. At the center of Mother Dwarf's world and her artwork is family. However, she handles this conventional subject in an unsentimental manner. Her son Vincent, who committed suicide more than a decade ago, is frequently present in her collages. Cat Box deals with her son's life, and acknowledges the strong connection between him and her husband, Ralph (the title of the piece refers to Vincent's nickname, which was "Cat.") Mementos of Vincent's childhood - grade school report cards and certificates, school photos, and handwritten notes - commingle with a photograph of her husband and son together, and a business card with Vincent and Ralph's names on it. Her sense of maternal loss is evoked by a white baby doll arm, which emerges from a baby cup and is swathed by a bracelet of green glass hearts. Cat Box was made in homage to Vincent, and to a lesser degree, Ralph. But through it, one gets a sense of Mother Dwarf's fortitude through emotional adversity. The work is not necessarily a celebration of the lives of these two men. Rather, it is an acknowledgement of their existence, and of their relationship to each other. Ultimately, however, one gets the sense that Mother Dwarf was not privy to this bond between father and son. Blue Velvet references filmmaker David Lynch, but a focal point of the piece is an altered black-and-white photograph of Mother Dwarf's son, Steven. In regard to the work, Steven says, "I think that's because we're both huge David Lynch fans." Yet there is something inherently sinister about the piece. A white, red-haired gaily-colored cartoon fairy princess in the foreground is seemingly being stalked by the menacing image of Steven's head. In contrast to the vibrancy of the princess, only Steven's eyes are colored; they have been changed to a fiery shade of red. This dichotomy is reminiscent of Lynch's obsession with innocent wholesomeness versus surreptitious - or, at times, overt - evil. And, as with Lynch, there is always more to the story than meets the eye. It is what lies deep within that reveals truths, even the most unsavory. Yet in Mother Dwarf's version of Blue Velvet, a fanciful city skyline with buildings reminiscent of grand mosques or temples of the East separates the beautiful fairy princess and Steven's predatory presence. Perhaps in this artist's world, goodness and beauty are not enervated or conquered by portending darkness. Mother Dwarf's family is not the only subject of her collages. CanCan is centered on seven pearly-white Barbie doll legs, each accentuated with glittery garter belts. The legs jut from two artificial pink roses, which are accentuated by strands of faux pearls. The dismembered limbs evoke the whirl of Las Vegas showgirls as they do the high lick on stage. Mother Dwarf clearly relates to this iconography, as she raised her family in Nevada and lived there until she moved to Cleveland after her husband died. However, the work straightforwardly acknowledges the dualistic nature of women's bodies and body parts; women's bodies imbue them with a degree of sexual power, yet when their "parts" are objectified or - as in the case of the showgirls - commodified, this power is undermined, even obliterated. The perfect long, slender Barbie doll legs are, of course, a myth; this is underscored by the blatant artificiality of the flowers and pearls. And, as 79-year-old Mother Dwarf knows, even if you could have them, they wouldn't last forever. Some of the most successful works in the exhibition are functional objects, including an end table and a night stand, which are seamlessly collaged with comic book and cartoon heroes, ranging from Brain of the Pinky and the Brain to Spiderman, as well as several fictional female heroines. Mother Dwarf's talent for flawless composition is fully apparent in these works. The pop culture imagery serves solely as "paint." "Aside from Spiderman, she doesn't even know who most the characters are," says Steven. Based on her artwork, Mother Dwarf seems to be a powerful, prolific character in her own right. Lyz Bly's review Once Upon A Time: Works by Mother Dwarf May 8 - June 11, 2005 Brandt Gallery 1028 Kenilworth Ave, Tremont OH 44113 U.S.A. |

Once Upon A Time show card and Angle ad

Lost & Found - 42 pieces May 8 thru June 11, 2004

Lost & Found opening reception shots

fotos/webwork by son of Dwarf

agent of chaos

what's new?

foto fable

artcrimes

collage

poetry

smith's top ten

poems - collages - illustrations - fotos

search Agent of Chaos website

site map